Hedges and screening

|

In the winter when the garden sleeps and the sun seems to be level with the horizon, this is the time when you pick up the detail in your garden, - the grainy pattern provided by a wooden gate, or the ripples on the paving slabs are clearly visible under winter’s spotlight, and suddenly your plot seems larger and emptier, so this is a good moment to plug any gaps, or plant a hedge, or screen an eyesore. You can plant in winter, with one major proviso. The ground must always be frost-free. If you live in a colder part of the country, you can get round the problem by preparing the soil in clement weather and covering it up with cardboard or old carpet to keep frost at bay. Then when your treasures arrive they can go straight in. If preparing the ground proves impossible and you’ve ordered bare-root, open your plants straight away and place them in a cool, frost-free place with some damp newspaper, or similar, round their roots. Alternatively pop them into a pot with some compost and water once every so often. As they’re dormant, they can survive for a month or two at least if the roots are damp. Potfuls can be put in a very sheltered place against the house, away from rain..

Planting tips

Hawthorn or May (Crataegus monogyna) is a British native with a special affinity to British wildlife so this is the best hedge to plant if you’re ecologically minded. In theory hawthorn can attract 150 different insect species, in fact it’s second only to oak in this respect. Visiting insects will sustain insectivorous birds and these may even nest in your hedge once it thickens and matures. The lobed leaves appear in spring, followed by insect-friendly cream-white heads of flower that smell of wine and cake. Red haws follow and these are appreciated by birds and small mammals.

Hawthorn makes a thick barrier but it will survive with a once-yearly trim preferably carried out once the red haws have been eaten. Whips, small twiggy plants, are sent out between November and March and these have been field-grown in rich-Herefordshire soil from British eco-types. Provenance is important, because foreign whips raised in colder parts of Europe will not flower at the same time as British-grown whips. They are out of sync with our wildlife. Each whip needs to be planted twelve inches apart (30cm) and, because the whips are small, they suffer no check in their growth and will race away once spring arrives.

Hawthorn is moderately vigorous and will make a hedge after six years. It’s tempting to buy larger plants to make it all happen sooner. However larger specimens of anything always suffer a check before they decide to grow. It’s counter intuitive, but in the long term, smaller is better when it comes to hedging and many other woody plants.

For faster results plant a double row and alternate them so that the one in the back row lies between the two in the front row, the three forming an equilateral triangle. Use a line, string between two sticks will do, and plant into well-dug enriched soil. Compost is best, but a slow release fertiliser (like Vitax Q4) will also work. Make sure you’re planting to the correct depth, so that the soil in the pot lies level with the soil in the ground. If it’s bare root, the line of dark wood will be clearly visible on the stem. Spread out the roots carefully into the planting hole. Cover the roots and gently firm in with your feet. Water in dry spells during the first growing season.

Hornbeam versus Beech

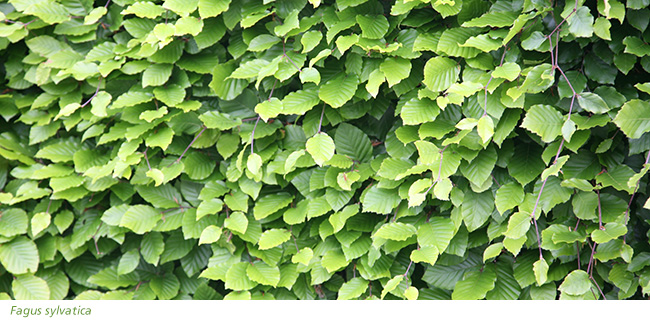

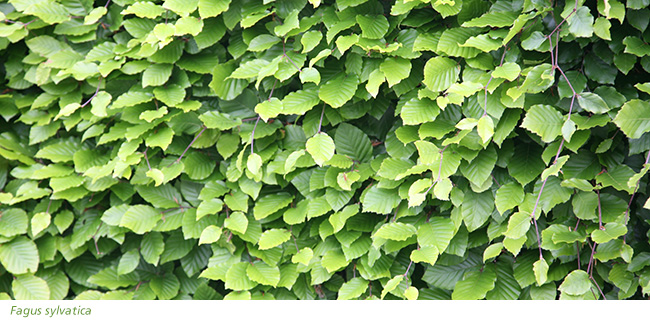

At first site beech and hornbeam look similar, both bearing oval green leaves. However in one respect they are entirely different. Hornbeam (Carpinus betulus) comes into leaf earlier than beech (Fagus sylvatica), by three to four weeks, and will begin to leaf up in late-April. It’s the perfect backdrop for spring-flowering plants including tulips because it’s already leafing up as they flower.

Beech is always later and holds on to some brown leaf, particularly when cut in August. On a cruel April day (and there are always some) the dry leaves rustle like old bones giving me the shivers. So hornbeam gets my vote over beech for its ability to leaf up much earlier. However once beech does come into leaf it delivers the freshest, greenest foliage of all - just as native bluebells open.

Hornbeam foliage is more rugged with very obvious toothing round the edge and veining. It’s the plant equivalent of crinkle-cut crisps. Beech has softer foliage, with a flatter profile, edged in soft whiskers or hairs. Stroking beech foliage is like handling fine silk underwear - warm and soothing to the touch. Both have grey wood and both can be grown as trees, in parkland though and not gardens. When it comes to pleaching, that’s hedges on stilts to most, the hornbeam wins again.

Soil and Conditions

The debate between hornbeam and beech may be academic in any case, because your soil may decide which to grow for you. Hornbeam relishes moisture and good soil and it would be an uphill struggle, some would even say cruelty, to plant hornbeam on chalk, or in dry and parched places. Beech copes with freer draining soil on chalk and limestone - and the shiny chestnut-coloured bud cases gleam in winter light, above a smooth elephant-grey trunk.

Mixed Hedges

Edible hedges work well when a mixture of British natives are grown together in one hedge, so you could use hawthorn with beech or hornbeam, or both, and add a field acer (Acer campestre). It’s our only native maple and it’s often found on chalky downland, although it is pollution tolerant. It’s often the gloriously golden tree you drive past in October but it could be trimmed into the hedge or left to grow. It’s fast growing so field maple is often spaced eighteen inches apart (45cm). You could also weave in some dog roses (Rosa canina). Single pink flowers appear in early June and red hips follow, but the dog rose is thorny. Sometimes a thorny hedge can be a great deterrent. The dog rose produces long twiggy growths when young, but just tip them back and this will encourage the hedge to thicken up. The hips, small and shapely like a maiden’s lips, are sensational in winter light.

Edible hedges work well when a mixture of British natives are grown together in one hedge, so you could use hawthorn with beech or hornbeam, or both, and add a field acer (Acer campestre). It’s our only native maple and it’s often found on chalky downland, although it is pollution tolerant. It’s often the gloriously golden tree you drive past in October but it could be trimmed into the hedge or left to grow. It’s fast growing so field maple is often spaced eighteen inches apart (45cm). You could also weave in some dog roses (Rosa canina). Single pink flowers appear in early June and red hips follow, but the dog rose is thorny. Sometimes a thorny hedge can be a great deterrent. The dog rose produces long twiggy growths when young, but just tip them back and this will encourage the hedge to thicken up. The hips, small and shapely like a maiden’s lips, are sensational in winter light.

A slightly more substantial rose often used for hedging is Rosa rugosa, a Japanese species that tolerates poor soil. Growing on sand dunes in its native Japan, it has large bright green leaves on a thorny bush. Rotund hips follow by September although the hips on the all white form ‘Alba’ are pale orange. The single pink form has darker hips. Both form upright, slender hedges quickly and grow on a variety of soils. However when grown on alkaline soil the foliage yellows and plants lose vigour. Shape and prune in winter. You’ll find a living breathing barrier much more eco-friendly and more comely to look at than a plain fence.

Top Hedge Tip

When growing a hedge let it attain the full height before you take anything off the top. You can trim the sides, to add extra bushiness, but don’t lop the top until it’s got there and then it can be cut back.