Pumpkins

Look what I found in the pumpkin patch.

Isn’t it the fattest, plumpest, most pumpkiny pumpkin you ever did see?

You can probably guess I’m inordinately proud of it: I suspect it may even be the biggest pumpkin I’ve ever grown. I even measured it: 115cm – that’s nearly four feet – around the girth, in case you’re interested. I don’t have the scales to weigh it, even if I could lift it up, which I can’t.

You can probably guess I’m inordinately proud of it: I suspect it may even be the biggest pumpkin I’ve ever grown. I even measured it: 115cm – that’s nearly four feet – around the girth, in case you’re interested. I don’t have the scales to weigh it, even if I could lift it up, which I can’t.

Actually, you can work out a guesstimate of the weight of a pumpkin from its circumference: an even better way is to measure its OTT (Over The Top) – the distance from blossom end to stem end, plus the distance from the ground on one side, across the top of the pumpkin to the ground on the other. You then use the figures with an 'OTT table' to figure out the weight of your pumpkin.

Or, if you’re me and can’t be bothered and don’t in any case need to know to the nearest ounce, just measure your circumference and use a 'circumference chart' instead. By this reckoning my baby weighs a cool 18.3kg (40.3lbs). Not bad.

Growing big pumpkins, rather like producing 11ft sunflowers or mind-blowingly fat marrows, defies all logic. What I’m going to do with the best part of 40 lbs of pumpkin flesh I have no idea. I don’t even like pumpkin that much. But I don’t care: it’s so damn satisfying.

I’m hoping this one might change my mind about the eating value, mind you. Of course, my ‘giant’ is puny compared to the real monsters, the Hundredweights and what have you.

Before I cut it away to bear triumphantly into the kitchen, though, there’s some work to be done. Pumpkins have quite soft skins at this stage in their growing lives, and if you’re going to store them for any length of time you have to ‘cure’, or ripen, the outer layer so it hardens into a carapace protecting the flesh within. Do it properly, and your pumpkin will last for months and months – I’ve used particularly good keepers in late spring before with no appreciable loss of freshness.

Before I cut it away to bear triumphantly into the kitchen, though, there’s some work to be done. Pumpkins have quite soft skins at this stage in their growing lives, and if you’re going to store them for any length of time you have to ‘cure’, or ripen, the outer layer so it hardens into a carapace protecting the flesh within. Do it properly, and your pumpkin will last for months and months – I’ve used particularly good keepers in late spring before with no appreciable loss of freshness.

This technique works for winter squash, too, though some (like butternuts) store less well than others (like Turk’s Turban, perhaps, or Kabocha). When I say less well, I mean for three months rather than six; so just eat your stored butternuts first and you’ll never even notice.

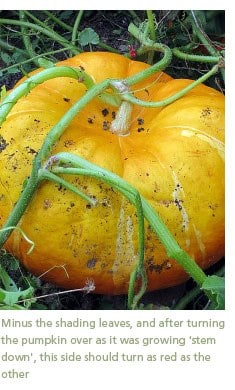

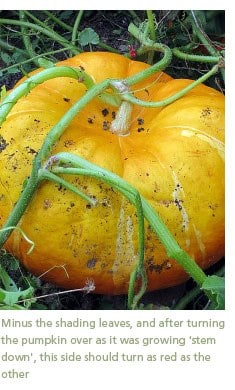

1: Remove the leaves covering your fruit so it’s fully exposed to the sun. Don’t completely strip the plant: just remove enough leaves to expose your fruit.

2: Hitch the fruit up onto bricks, bits of wood or whatever you have to hand: a pallet works well for really huge pumpkins. The idea is that you lift the skin clear of the ground (and therefore slugs and dampness can’t damage it) – and at the same time allow air to circulate underneath too.

3: Turn smaller pumpkins and squashes by about a quarter every few days, to ripen the fruit evenly (to avoid twisting the stem right off, just revolve it 180 degrees one way, then 180 degrees back again).  I’ve never quite figured out how you’re supposed to do this with a giant pumpkin: my guess is, judging by the undeniably squished shape of most whoppers, you don’t.

I’ve never quite figured out how you’re supposed to do this with a giant pumpkin: my guess is, judging by the undeniably squished shape of most whoppers, you don’t.

4: If you haven’t already pinched out smaller fruits through the season, do so now. You want to leave around three or four maturing fruits on your vine and remove any pale, small fruits now: they’ll never reach full size anyway, given how late in the season it is, and you want your plant concentrating all its efforts on the fruit it already has.

5: After a couple of weeks of this, the colour should be fully developed – deep burnt red for a ‘Rouge Vif’s or a lovely warm orange for Hundredweights and Autumn Giants – and the fruit should sound hollow when you knock it. The stem may be starting to look a little shrivelled and dry too. At this point, cut the fruit with around 10cm of stem and bring it indoors to keep somewhere cool (but frost free) and dry.

You can probably guess I’m inordinately proud of it: I suspect it may even be the biggest

You can probably guess I’m inordinately proud of it: I suspect it may even be the biggest  Before I cut it away to bear triumphantly into the kitchen, though, there’s some work to be done.

Before I cut it away to bear triumphantly into the kitchen, though, there’s some work to be done.  I’ve never quite figured out how you’re supposed to do this with a giant

I’ve never quite figured out how you’re supposed to do this with a giant