|

So often we concentrate on flowers, wanting a riot of colour in our gardens that we forget the beauty of foliage, but we need foliage to offset the mass of colour, and counterbalance all that razzle dazzle.

Leaves comes in an abundance of colours, shapes and sizes, from the simple bold heart-shaped hosta leaf to a decorative filigree-like leaf of a ferns. Hardy ferns have some of the most intricate foliage of all. Their fronds unfurl, generally in spring, to reveal bristled stems and then their lacy crosiers unfold before your eyes. They don’t produce flowers at all, because ferns generally evolved before the bee and other pollinators arrived, some 360 million years ago. Ferns are reproduced naturally from spores, or bulbils on the fronds, or you can propagate some by division by splitting the crowns in early spring. The rare ones have never been widely available, but in recent years ferns have been micropropagated, making some of the rarities more available. Micro-prop has also produced some new ones.

Ferns generally adore shade and perhaps it’s because they began life in the primeval forests. They make excellent plants for a woodland border or shady corner. Their simple genetic structure produces lots of variation in the fronds and certain names crop up again and again to describe the differences. Cristate or cristata means that fronds are topped in leafy crests. Congestum means crowded with lots of smaller leaflets. Crispum is frilly-edged. Crenatum is scallop-shaped. Grandiceps has fronds that are larger than normal.

The Victorians, especially women, were fern fanatics and they collected unusual ferns from wild sites throughout London and in the western half of Britain. The age of pteridomania, or fern mania, lasted between 1850 and 1890, and fern motifs popped up on garden benches, pottery, glasses and clothing. Many Victorian gardeners grew their ferns in fern houses and terrariums to recreate the romantic landscape which so many of them had left to come to the cities and towns.

As a result lots of British ferns have the collector’s name attached, such as ‘Martindale’, ‘Barnesii, ‘Bevis’ or ‘Stablerii’. Others are named after the places where they were found such as Axminster. Many ferns were over collected and appeared to disappear. However they often came back after a period of time because the juvenile phase of the fern is rather similar to liverwort. Ferns are also found across the world and these have been introduced into Britain.

The Five Main Wintergreen Hardy Ferns

There are five hardy wintergreen garden ferns suited to shady places.

Dryopteris

This group (Dryopteris) has the largest number of good garden ferns and nearly all have fiddle-neck crosiers that unfurl in spring at roughly the moment British bluebells flower. They are handsome and upright and most are extremely easy. The male fern (Dryopteris filix-mas) is found in deep shade in British woodlands. It’s erect and robust, hence the name male fern, and it will grow in deep fairly dry shade. The cristate form, D. filix-mas ‘Cristata’, has feathery tips to the ends of the fronds and is a paler green. Both are best grown in deep shade.

The golden male fern, D. affinis, tolerates far more sun than D. filix-mas so it’s useful in partly shaded areas where hellebores might be growing along with other woodlanders. It’s more elegant and slender in form, often with golden bristled stems. There is also a crested form named ‘Cristata’ and both will unfurl their fiddle-necked fronds in spring. The golden male fern, D. affinis, tolerates far more sun than D. filix-mas so it’s useful in partly shaded areas where hellebores might be growing along with other woodlanders. It’s more elegant and slender in form, often with golden bristled stems. There is also a crested form named ‘Cristata’ and both will unfurl their fiddle-necked fronds in spring.

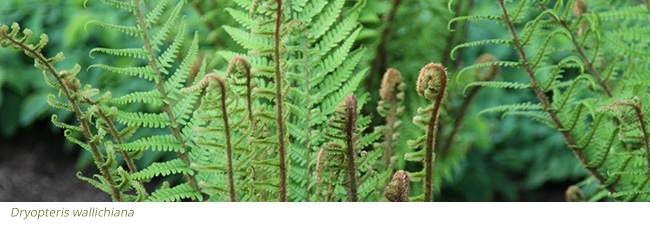

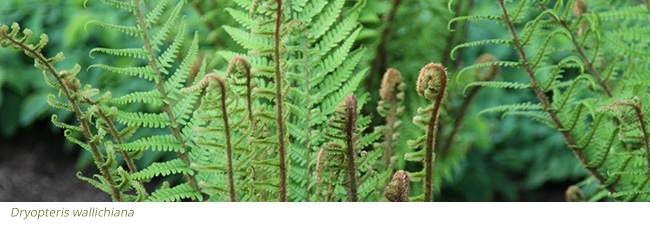

One of the most dramatic ferns is Dryopteris wallichiana and the Himalayan form, first collected by Nathaniel Wallich in the 1830’s, has dramatic black bristles and bright green foliage. The crosiers have very curly tips. This fern prefers moist but well-drained soil and will become lavish and handsome in time. It will tolerate deep shade, but it’s not for dry shade.

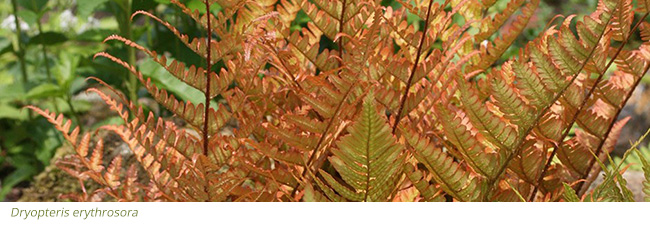

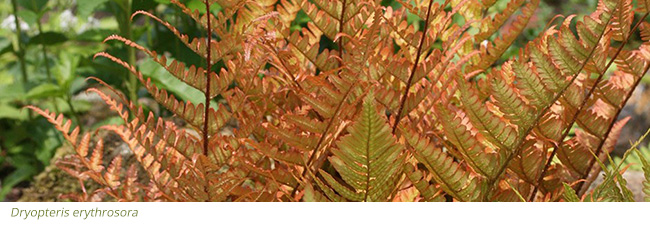

Dryopteris erythrosora, the autumn fern, spreads by underground stems so it’s lower growing. The new fronds emerge in spring and are pink with red backs, so it’s an excellent foil for snowdrops and blue scillas. In autumn this Asian fern, found in Japan, China and Taiwan, colours up to gold and that’s why it’s known as the autumn fern. This lower-growing fern does well on a bank.

Generally most dryopteris are cut back in late autumn to reveal the brown knuckles of next year’s fronds and these nobbly knuckles can look very handsome in winter.

Polystichum

Polystichums, their name meaning many-bristled to reflect the rust-coloured hairs on the stems, have intricate, almost mossy foliage that can suffer if heavy rainfall strikes so they need careful positioning, against a wall for instance. The stems are heavily bristled, usually in rust-brown, and the new s-shaped fronds appear when the erythroniums are out in April, almost looking as they have been crocheted. The common name of P. setiferum is the soft shield fern and many cultivars have been named. One of the mossiest of all is Polystichum setiferum Plumosomultilobum Group and the fronds look almost look 3-D in profile. These ferns have a wider than taller shape and in most winters the foliage will look handsome, so P. setiferum is usually tidied in spring as the fronds can brown in hard weather. ‘Herrenhausen’ is one of the neatest, with dark green fronds that show off the rust-brown bristles. The ends of the fronds are tightly curled and the colour of raw silk.

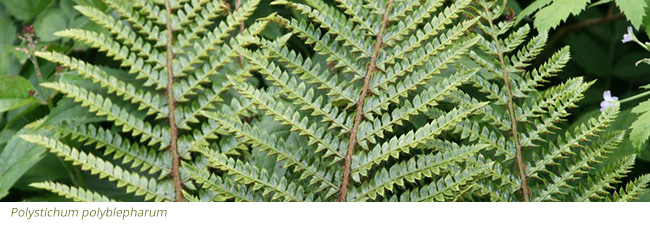

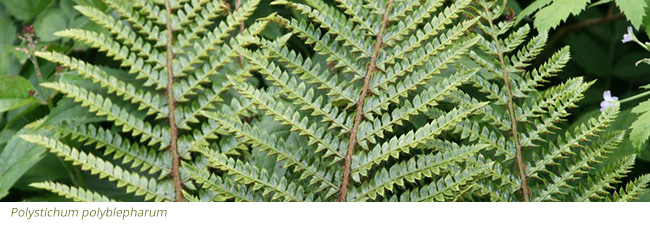

Other forms of polystichum include the hard shield fern (P. aculeatum). This has much stiffer foliage, and although the top of the frond is shiny, the underside is very matt. This fern is perfect on a shady bank. There’s also the Japanese tassel fern (Polystichum polyblepharum) and this has dark blue-green foliage in summer. Although this is an evergreen fern, the foliage does disappear in hard winters. P. munitum, from north-west America, is a very large handsome fern with a slightly loose habit.

Polypodium Polypodium

Polypodiums have leathery, shiny fronds that are usually simple in structure. Their name means multi-footed because they produce creeping rhizomes. They must have good drainage and an airy situation to prevent the fronds from getting too moisture-laden and heavy so they often colonise walls and stonework. They actively dislike humid, damp spots but these shorter ferns are a bright green. Polypodies have a period of summer dormancy and the fronds tend to brown. They start up again in late summer, their curly fronds making an s shape. Tidy in early summer and don’t be afraid to cut back brown fronds in summer. The fern isn’t dead, it’s just having a sleep.

Asplenium Asplenium

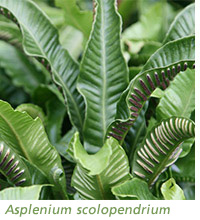

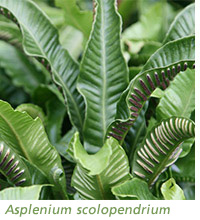

The hart’s tongue ferns, forms of Asplenium scolopendrium, have solid tongue-shaped fronds which scorch easily in sunlight and wind, so you must find these a fully shady, sheltered position. If you can find the correct spot, a warmly sheltered one in complete shade, they shine in winter. They like being tucked away at the back of shady borders.

Athyrium Athyrium

Athyriums tend to be delicate, lacy affairs, so much so that Athyrium filix-femina is known as the lady fern. They are robust, but need moisture and shade to do well and can suffer horribly in dry summers. The Japanese painted fern (Athyrium niponicum var. pictum) has silvered fronds and reddish stems. It enjoys summer moisture, shade and shelter.

Blechnum Blechnum

Blechnums are mainly evergreen ferns, but they will only thrive in neutral to acidic soil, although you could pot them up into containers containing ericaceous compost. These tapered slender ferns have erect, very leathery fronds and this gives them an ultra-neat look.

Deciduous Ferns

Deciduous ferns, ones that die away in winter, tend to be thirsty plants. They produce shuttlecocks of crosiers, with a definite middle, and are often grown near ponds but always above the water line. The regal or royal fern (Osmunda regalis) is a majestic sight by early summer when the upright fronds are a bright grass-green. The new crosiers are a dusky purple and by autumn the fronds have turned to butter-yellow, so this is a plant chameleon. Deciduous ferns, ones that die away in winter, tend to be thirsty plants. They produce shuttlecocks of crosiers, with a definite middle, and are often grown near ponds but always above the water line. The regal or royal fern (Osmunda regalis) is a majestic sight by early summer when the upright fronds are a bright grass-green. The new crosiers are a dusky purple and by autumn the fronds have turned to butter-yellow, so this is a plant chameleon.

The true shuttlecock fern (Matteuccia struthiopteris) loves shade and moisture and is often planted in bog gardens as a backdrop for showy bog primulas such as Primula japonica 'Miller's Crimson’. It’s wonderfully symmetrical and it sits above ground, with the stolon beneath, so it could also be grown in wilder areas.

When it comes to planting, ferns look best in quiet areas with other green foliage plants that might include the pretty wood millet, Melica altissima ‘Alba’. They also make perfect partners for woodlanders such as hostas, hellebores, geraniums and foxgloves.

|